I first came across A.S. Neill when I embarked on my doctoral research programme. At the time, there was a dearth of accessible playwork literature, and I was curious to find out what playworkers were reading and where they were getting their ideas from. So I set up a small survey and found that many of the respondents had been inspired by Neill’s (1962) book Summerhill, and that they particularly identified with his philosophy on children and childhood. Like many new PhD researchers (and an English graduate to boot), I was thrilled at being given licence to read anything that interested me in the name of ‘research’. So I added Neill’s significant body of work to my reading list, but was reluctantly dragged from the depths of my cosy literature pit by my diligent supervisor before I had had the chance to get anywhere near it.

I then carried out a more in-depth literature search to find out what writing had been produced by the adventure playground pioneers themselves, and lo and behold, up popped A.S. Neill again! As it turned out, it wasn’t only my contemporary playwork peers who had been inspired by Neill’s philosophy on childhood. In 1961, Sheila Beskine reflected on her role as an adventure playground worker and how she, “simply by being there”, enabled the children to learn and discover for themselves. She observed that education might benefit from adopting “this voluntary principle instead of that of the policeman” and cited Neill. I’m also interested in whether Lady Allen of Hurtwood, one of the chief movers and shakers behind hundreds of adventure playgrounds across the UK in the 1960s and 70s, was influenced by Summerhill. As a former pupil of the ‘progressive’ Bedales school herself, and a self-confessed ‘borrower of ideas’, much of Lady Allen’s philosophy on childhood and children resonate soundly with contemporaneous ideas on alternative education, “Every child is an individual marvel, gifted with unique capacities, ready to respond to those who trust them and to those who have no fear of giving them freedom” (Allen and Nicholson, 1975).

Fast forward to the present and I have to confess that A.S. Neill’s work remains on my (ever expanding!) reading list. Sadly, it doesn’t look like I’m going to get to it any time soon, thanks to the immense interest in the PARS model of playwork practice which I ended up developing as part of my doctorate. So I am enormously excited to have A.S. Neill back in my life once again, through an invitation to present at the Summerhill Festival, online at the end of September and then in person (and in a field!) next summer. Whilst my knowledge about Neill’s work and ‘alternative education’ is still very much at an embryonic stage, I am thoroughly enjoying exploring the parallels between the adventure playground pioneer’s philosophy on childhood (defined as ‘childist’ (Wall, 2007) in the PARS model) and Neill’s vision for childhood which led to the creation of Summerhill. Both radical in their time and still regarded as radical today in some circles, both have attracted their devotees and detractors. As Lady Allen (1975) opined in her autobiography, “We were freely accused of being anarchists or communists, and of undermining morals…”.

One of the reasons that the adventure playground pioneers and A.S. Neill attracted criticism was that they held a mirror up to the adult world and asked whether the adult world was happy with what it saw when it came to the state of childhood. There was also often an indirect – or sometimes rather pointed – inference that not only had the adult world created problems for children, but that it was constantly failing to do anything about those problems. Reflecting the terminology of the time, Neill followed up his book ‘The Problem Child’ (1926) with ‘The Problem Parent’ (1932) and even ‘The Problem Teacher’ (1939). The very titles of these books provide (both then and now) a deliberate provocation to the established order of adults always being in the right and therefore deserving of unquestioning respect. In a similar vein, the adventure playground pioneers abhorred the contemporaneous term ‘juvenile delinquency’, turning it on its head to point to “the adult delinquents” (Lady Allen, n.d.) instead. In 1965, a report by adventure playground worker Donne Buck couldn’t have made the point any clearer, “I am often asked how I think Adventure Playgrounds can prevent Juvenile Delinquency. Well, for a start, I don’t like this terminology; I think it should be Juvenile Rebellion, against ill informed and generally biased adult minds.” For the adventure playground pioneers and for Neill, the question of who was ‘right’ was literally a matter of perspective – the children’s or the adult’s. One of their great frustrations was that much of the adult world simply couldn’t (or wouldn’t) see it the same way.

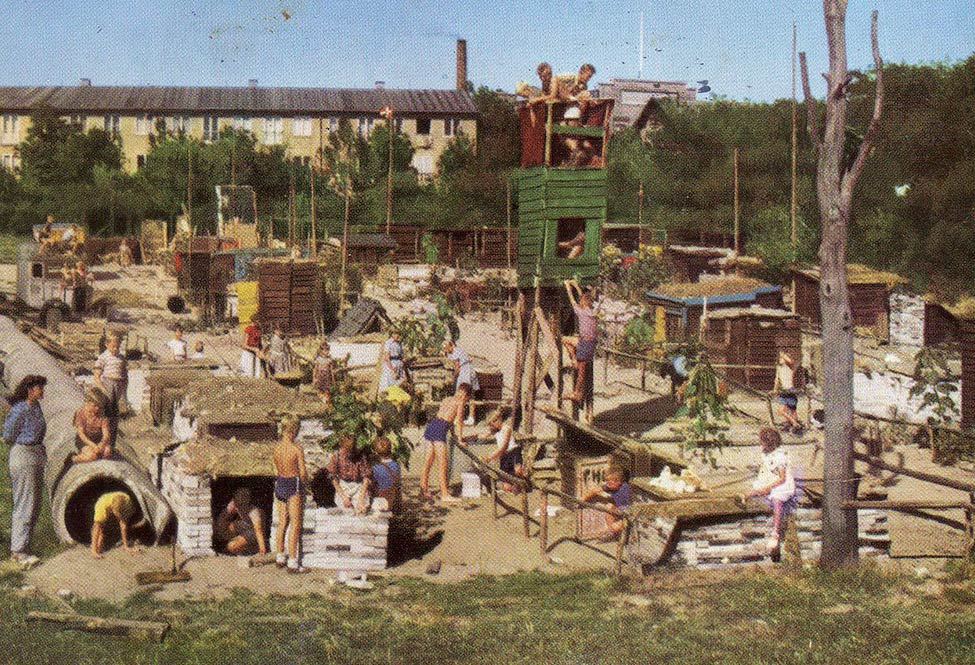

Neill and the adventure playground pioneers viewed childhood as a distinct period of time which had its own laws and lores. For them, it was vitally important for children’s well-being that adults should recognise childhood as a separate state of being, and also make this belief manifest in all their dealings with children. Neill applied his philosophical approach to childhood to the domain of education, setting up Summerhill as a school designed to fit children, rather than an adult-designed standard educational system which tried to make children fit. Working in the domain of children’s leisure time, the adventure playground pioneers scorned the standard ‘slide, swing and roundabout’ playground, described by Lady Allen (1964) as “an administrator’s heaven and a child’s hell”. Adventure playgrounds were specifically designed as “permanent places of change” (Abernethy, 1968): spaces which were created and run on a minute-by-minute, day-to-day basis by children. It was impossible to produce a “blueprint” for an adventure playground (Lambert, 1974), as every single one was an individual creation of the personalities, interests and imaginations of the children who used it.

Like A.S. Neill, the adventure playground pioneers firmly believed that children should be free from adult authority, at least for some of the time. As the Danish inventor of the adventure playground concept, Carl Theodor Sørensen (1947), put it, children “… to the greatest possible extent ought to be free and by themselves….I am firmly convinced that one ought to be exceedingly careful when interfering the childrens lives and activities” (sic). However, the early adventure playground workers became uncomfortably aware of a flaw in trying to enact their philosophy on childhood through the provision of adventure playgrounds. Although adventure playgrounds had initially been trialled without adults, it was found that adults were in fact necessary; to open and close them, to resource them, to repair them, and to defend them from their (adult) critics and thieves. The early adventure playground workers also discovered, somewhat to their surprise, that sometimes adults were needed by the children themselves; “I was needed everywhere – to provide materials, settle disputes, answer questions, take an interest and give first-aid to some very minor injuries” (Turner, 1961). Sometimes children just needed adults to “sit on their backsides and talk” (Balmforth, 1979). This tension between the ideological desire for children to have time and space to enjoy their childhood on their own terms, the operational requirements of the adventure playgrounds and the practical and emotional needs of the children created a conundrum for the early adventure playground workers. How could adults be helpful in a child’s world without unnecessarily imposing adult strictures or importing adult concepts which would destroy it?

Creative solutions are often born out of seemingly intractable problems, and out of the adventure playground pioneer’s philosophical and practical dilemma came the “unorthodox recipe” (Turner, 1961) of playwork. PARS playwork practitioners recognise that children have a right to time and space to be children and to enjoy their childhood as a distinct and unique life stage. Children “have a different and equally valid viewpoint” (Mays, 1957) and therefore, as adults in children’s time and space, “It is not possible to be always right and it is more important to be readily responsive.” (Turner, 1961). However, PARS practitioners also recognise that adults in children’s time and space inevitably have some sort of ethical, moral, regulatory and legal obligations. The PARS model of playwork practice therefore empowers adults who work in children’s time and space to compensate children for the presence of adults whenever possible, whilst ensuring that necessary adult input respects the unique knowledge and experience of childhood.

I am so looking forward to learning more about A.S. Neill at the Summerhill Festival and how his philosophy has inspired thousands of people and projects around the world. For my own small part, I will be talking about the PARS approach to childhood in theory and in practice with some of our fantastic international PARS Licensed Trainers (and I do hope that A.S. Neill would approve!).

PS As this is a blog, I haven’t added a reference list. However, please do contact me if you would like one and I will gladly email it to you!